PART 1 : Finding Louisette

Halfway through the 1950 classic Hollywood movie “All About Eve,” Margo Channing, played by Bette Davis, exits her own cocktail party after tossing back a martini, walks past her fiancé and friends, mounts the stairs, and delivers the show stopper. “Fasten your seatbelts it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

I was having a martini and watching the movie last night and when I heard that line, I thought of Louisette Texier, a centenaire who we interviewed in 2019. Louisette and Bette could have been best friends. It’s easy to imagine them sitting together in a booth at the Stork Club or at El Morocco in New York. I was behind in my writing but Louisette Texier’s life was a great script waiting to be written. It had everything: love, beauty, drama, adventure, exotic locations, and daring escapades in fast cars. She was a strong woman in charge of her life and she lived her life on her own terms.

Margo, Bette’s and Louisette’s life all had bumpy rides just different kinds. In the movie, Margo’s bumpy ride was a rollercoaster of betrayal and deceit behind the stage door of life in the New York theater world. Bette’s life was one of stratospheric professional achievement and personal wreckage who ultimately triumphed over adversity through sheer force of will. Louisette took the bumps in life driving her Jaguar MK2 on the open road in rally races around the world during her forty years as a champion driver.

Louisette lives outside Agen in southwestern France at the Residence Saint-Jacques senior care facility. She has a small apartment. William said he was lucky to find a place for his mother that was a relatively short distance from his family’s home. We stopped at his home, a beam and glass, 1960’s style northern California hippie mansion – very Mamas and the Papas – before he drove us to the train station. The air smelled of lavender and cedarwood. Macrame dream catchers with feathers, hanging chairs, and mason jars with folded paper packets of tea leaves with labels like Sunset Kindness and Juniper Jazz filled the shelves. I shared with his wife memories of my own childhood visits to Big Sur with its pine forests and lavender covered slopes filling the hot afternoon air with intoxicating scent; I hadn’t thought about Nepenthe’s in the canyon where I got my first whiff of pot in years. The Texiers had a certain kind of California in their souls that I knew; they’d lived there for twenty-five years. I wanted to accept their invitation to stay and remember when I was a boy of thirteen.

Louisette has little memory of her life. She remembers her son William and counts on him. She can be prompted by showing her a photograph but she can barely vocalize any associated memories. She agrees, really consents in fact, to accept facts we knew and wanted her to confirm and elaborate on. We had a binder of information about her life gathered from published sources but there were large gaps. William relieved the slightly awkward, stilted atmosphere in the room in a cheerful way while he helped his mother along. He could get her rolling a bit during our visit but she could only roll a short way. He said that it wasn’t one of her better days. He had some papers at home that might help us with the gaps.

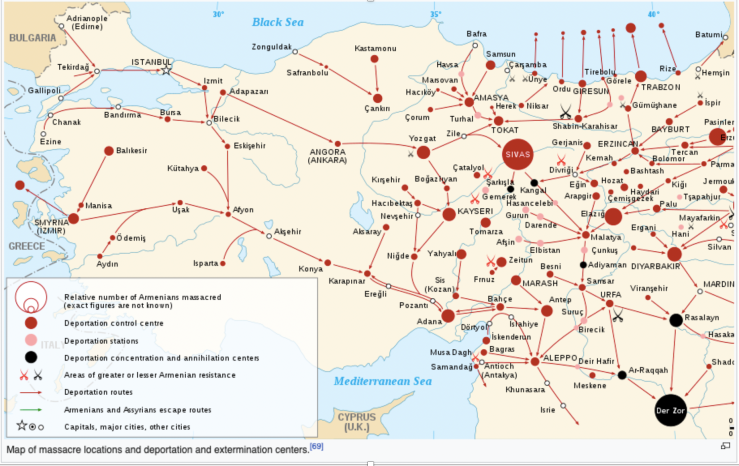

Knowledge of Louisette’s early life is fragmentary. Some events in her childhood are known, many of the basic factors that determine our identity and that we take for granted are, in Louisette’s case, unknown because her birth records, family name, school records, marriage certificates and such were altered or lost. What is known is that Louisette’s birthname is Arpine, her mother’s name was Macht and she had a sister named Mariam. Her last name is recorded as Hovanessian but William told us that even Hovanessian was probably not her real family name. It was probably chosen to hide her real identity after her father was hanged in 1915 along with the 1.5 million ethnic Armenians killed by the Ottomans. Even after Louisette and her mother and sister fled their home in Turkey, his name was potentially dangerous; the practice of changing names was not uncommon among Armenians exiled from Turkey who faced possible reprisals. From their home in Konya emigres were taken to Aksehir and then through a series of deportation control centers: Afyon, Eskisehir, the city of Bilecik where refugee where the routes from the south, east, and west assembled, then to Izmit or Bursa and across the Bosporus or the Sea of Marmara to Constantinople, the ancient city of Byzantium or, since 1930, modern-day Istanbul.

When they arrived, her mother put her two children in an orphanage for safety. An unknown non-for-profit organization deemed the orphanage unsafe. The organization sent Mariam to Greece and Louisette to Marseille where she was placed in another orphanage. At some point she was sent to a boarding school in Neuilly, a small district in northwestern Paris next to the Bois de Boulogne. That’s what has always been known and repeated. Those were the facts as it were. Though, as I would discover, the facts were an interpretation of the facts.

It frustrated me that there weren’t any specifics that could substantiate or help make sense of those years after she arrived in Istanbul, though I accepted the fact that sometimes in times of upheaval and displacement there’s nothing to be found. And yet, it felt as if there was something just below the surface and I bet my money on the notion that all things lost are waiting to be found.

For me, understanding the nuts and bolts of those years would make it easier to understand the part of her later life that is well known: racing cars. Maybe the nuts and bolts would answer why racing was so appealing? Not that exhilarating speed or the smell of burning gas and rubber aren’t an end in themselves, but why pursue it so avidly and relentlessly? And on a second front, why own clothing stores?

During the first weeks of the Covid-19 lockdown, I had plenty of time to review my research files and scrutinize the broad-brushed narrative of those years. I examined an eye numbing number of Internet sites for clues and piece by piece, and with a little inductive reasoning, a picture of what happened during those early years became evident.

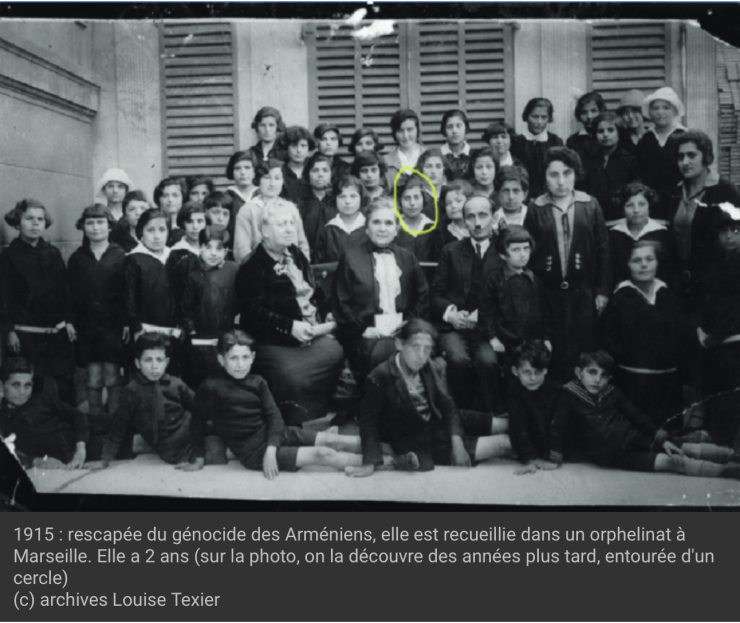

Macht put Louisette and Mariam in the Franco-Armenian Tebrotzassere School and orphanage system soon after they arrived; perhaps in 1916 or 1917 when they were about four and nine-years old respectively. Their first days at orphanage and their ages can only be approximated. The Tebrotzsassere, an educational facility and center for refugees offered, along with its other community activities, safe haven and education to children fleeing the genocide. Tebrotzassere wasn’t a roadside drop-off orphanage. The institution had the patronage of important members of the Armenian and French communities.

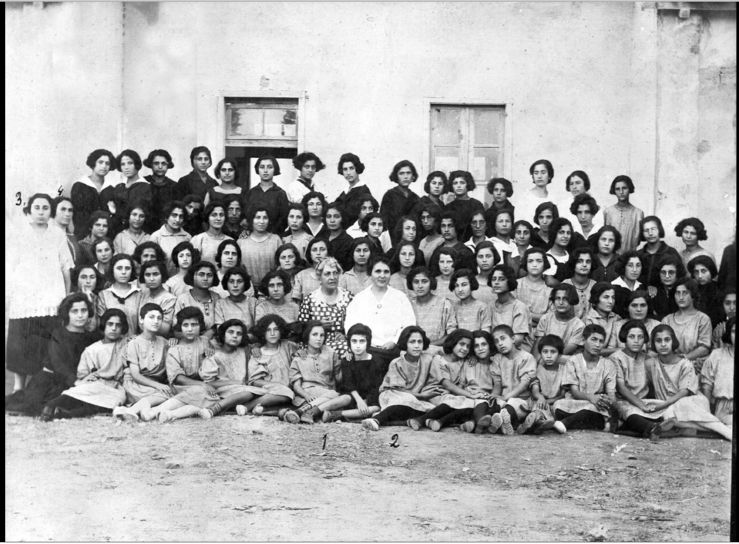

Mmes. Takouhie Balthazarian and Aguliné Boyadjian ran the not-for-profit institution. During the next few years the teachers and children had to move to four or five different host facilities within Istanbul; some were schools and other orphanages, and a couple were rented lodgings. In 1922 the school moved from the Koum-Kapou district to Thessalonica in Greece; roughly a 600-mile journey by land to Izmir and then by sea. Ninety-five children, including Louisette and Mariam, and two teachers occupied three single-story buildings in deleterious condition and it was quickly clear that the school needed to find a different more healthful and amenable arrangement. Thanks to the intervention a prominent Armenian politician residing in Paris, an archbishop, and a member of the French Foreign Service, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs granted the school a group visa allowing them to travel to Marseille in 1924.

Louisette can be recognized in a group photo with her classmates and teachers taken in Thessalonica in 1923. Mariam cannot be identified in the same photo with any precision. Louisette would have been about ten to twelve years old. She can be picked out of the group by comparing her likeness to one that William confirmed was his mother in another school photo taken in Marseille; William had drawn a small circle around his mother’s face. She’s flanked by forty-five or so other children, a few stern-faced adults, and stands in the second row behind a Mmes B. and B. The photo was most likely taken in 1927 or 1928 when she was about fourteen years old.

Mariam did not go with Louisette to Marseille. According to a letter from a cousin of William’s living in Plodiv, Bulgaria Mariam remained in Thessalonica until 1926 where she was tracked down by Macht’s third husband Asadur, the grandfather of Williams cousin; his search was aided by the Red Cross and Armenian church officials. At the time she was living as a novitiate in a monastery. Asadur adopted Mariam and they returned to Plodiv.

The foregoing itinerary and chronology would explain in part the mistaken generalization that the two went their separate ways in Istanbul.

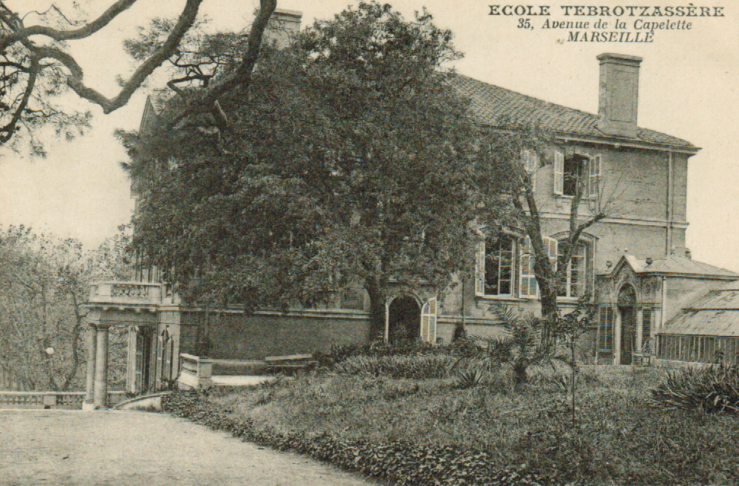

The school moved to Marseille in 1924 and established their new base of operations at 35, Ave. de la Capulette where it remained until 1928. The building was loaned to them; it was a large, block-cut limestone residential home with an impressive, pillared portico and greenhouse. It had a solid edifice suggesting permanence in comparison to the featureless storage-like structures in Greece that look more like temporary detention barracks. When the owner retook possession of the building, the school moved to a compact, four-story building at 1 Blvd du Nord in the suburb of Raincy outside Paris. These quarters were the final stop on the school’s long path to a reach permanent home and it was Louisette’s last digs before leaving the school in 1930 or thereabouts.

The well-repeated story that she went to a boarding house in Neuilly is mistaken in light of the foregoing although a confusion in place names is understandable. The boarding house is the school. Raincy and Neuilly sound roughly the same but in most other ways they are very different. The confusion in storylines is compounded by the verifiable fact that Louisette opened clothing stores in Neuilly many years later.

At fifteen, though she was probably seventeen or eighteen, she left the school, or as it’s been more colorfully described – she ran away – to dance in the cabarets of Paris. This is the most obscure period in her life story. She only remembers that she lived in Montmartre during that time. Travelling to Paris was easy; Raincy is just thirty minutes from Gard de l’Est by train and from there Montmartre is an easy walk.

On the wall in her apartment is, what has always been considered to be, a promotional photograph for an unknown cabaret. She is no longer a teenager. She is a beautiful young woman with thick, wavy, raven color hair, and dark eyes. Her persona is happy, confident, glamorous, and alluring. In the photograph she is partially reclined over a tambourine wearing a harem inspired, sequined and embroidered, two-piece costume with sheer sleeves and pendant earrings. She evinces the confidence of a movie star.

In the lower right-hand corner of the photo is the Studio Piaz logo stamp – TEDDY PIAZ, 122 Champs-Elysees, PARIS. His clientele were almost exclusively the most famous celebrities and personalities of the era: Josephine Baker, Edith Piaf, Jean Marais, Marlene Dietrich, Serge Lifar, Sophia Loren, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Charles De Gaulle; it’s a long and impressive list. Her portrait by Piaz makes it clear that Louisette was not your everyday cabaret dancer, she was a member of entertainment world’s upper echelon. But from there the trail goes cold.

When we showed her the photograph during the interview she recognized herself. She smiled broadly and appeared to remember the moment and the circumstances. We’d hoped the moment would drum up the names of clubs where she worked – The Lido, the Casino de Paris – or of any of the smaller venues throughout bohemian Montmartre. We asked her if she remembered other performers or friends from those days, but none were forthcoming. William asked a few times if she remembered a young woman from those years named Lumina who he’d met with her husband at some point while growing up but she didn’t seem to hear him, nothing registered, her expression was blank. Over coffee this morning, I looked through old newsreels and stills spotlighting exotic Eastern themes hoping I might get lucky and spot her. I didn’t.

It’s unknown when she left the cabarets to open a dress shop. The family says she was able to because she saved enough money from dancing and repairing costumes to leave the entertainment world and start a business.

She could draw on skills learned in childhood. William’s cousin wrote that the orphanage in Istanbul taught the children to sew. Today, the online history of the school confirms that in Marseille the children were also taught to sew and make clothes. Knowing that she had the necessary training helped make sense of how she could go into the clothing business.

William told us later that she retired when she was ninety-two. At the time she had three stores for women and a men’s shop located around Ave. Charles de Gaulle and Rue de Chartres in Neuilly. For reasons unknown to him, the womenswear stores were named Tex Ranch and she choose to call the men’s shop Tex Bond. James Bond? Fast cars, independent women, travel?

She didn’t seem to notice that Damian had been taking photos throughout the interview. When he asked her if he would sit for a traditional portrait, she had no problem being wheeled about to a better position in the fading, late afternoon light. She mustered a perky smile but maintained an apprehensive, who-are-you sort of look. His portrait is stunning, as in being hit over the head, and frank. He caught her frailty and the look in her eyes of drifting in an endless loop of endlessly knowing and not knowing.

The few existing details from her cabaret years, the years leading up to WWII through the mid-fifties when she began her racing career are now known only to William, his family and those years. Our time in Agen didn’t allow for us to explore those decades more thoroughly but we were invited to call or visit anytime. Facing my fourth week of lockdown, the idea of sprawling out in a lavender field watching bees looks good to me.

PART 3 : La Louisette

It’s hard as a biographer to leave a block of life unexplored. It feels like you are not doing your job. Like you’re leaving out the middle of a sentence: “The lighthouse beacon …. broken oars and splintered trunks littered the shore.” You can guess what happened from the context but you can’t really be sure. That’s why Part II is missing. Too much conjecture.

Chronicling her racing years is much easier than undertaking an archeological dig to find her childhood. The information is general but tidy, neatly arranged and there are plenty of photographic documents and eye-witness accounts.

Louisette’s passion for racing started in 1955, when George ‘Jojo’ Houel, a close and lifelong friend, invited her to go the Linas-Montlhery motor-racing track outside Paris on a Sunday afternoon in May.

That day she met Jean Behra, the world-class Formula One racecar driver who at the time was driving for Maserati. He conveyed his love of the sport with such all-embracing verve that the following January she entered the 1956 XXVI Monte Carlo Rally race with her partner Annie Soisbault with whom she would race beside for many years. They were accompanied by the veteran driver Germaine Rouault who Louisette had met a few days before the race at The Action motorhead bar. They finished 119th out of a field of 233 competitors in her Simca Aronde.

That April, she returned to Montlhery in her Simca and placed 6th in the Coupes de Vitesse; in August she drove 2,200 km from Deauville to Hyeres with Monique Bouvier in the Mobil-France Economy Run; and in October she took 13th place in the 16-lap Coupes de Salon at Montlhery on the extended closed-circuit course. From then on, her zeal for the sport became, in her own words, “a vice”.

“It was cars for me. Nothing else mattered.” she told Xavier during the interview. Cars and racing were the trigger that Xavier and William could use to bring her back from her solitary. Xavier ‘s questions seemed to tax her but she smiled when William showed her the trophy for taking 2nd place in the 12-hour endurance race at the 1959 Florida International Grand Prix at Sebring.

Fellow gas jockeys hanging out at The Action or The Steering Wheel sharing drinks and jokes dubbed her La Louisette or The Guillotine. It’s a witty riff on her name and the French slang word for the apparatus that chopped of King Louis XVI’s head – La Louisette. By changing the placement of the noun “tete” (head) in the phrase “La tete de Louis” and dropping the preposition “de” (of) you get the grammatically incorrect “La Louis tete” (The Louis’ head); drop the first “t” in “tete” and you are left with “La Louisete.”

Nicknames are common in every aspect of community life and the world of women’s racing since its inception was no exception. I got a kick out of two: Camille du Gast – The Valkyrie’s Mechanic and Fay Taylour – The Goddess of Gas. Louisette “The Bulldozer” Texier as she was known when she raced for Shell Oil, is an appellation of affection to be sure, but everyone’s, even non-sensical ones, tease a bit and express a morsel or more of truth.

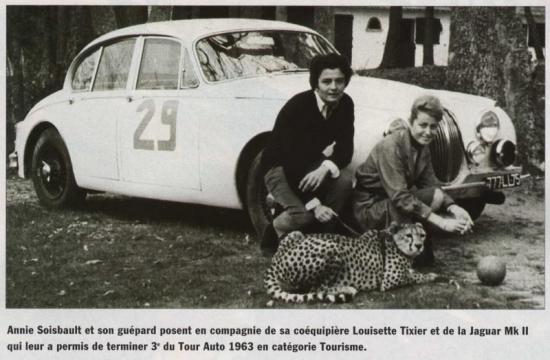

Louisette’s suggests a push-right-through, clear-a-path approach to driving and competition. But The Bulldozer was not a win-at-all-costs sort of person. She is described by those who knew her as being forthright, gregarious, honest, dynamic, and passionate about racing. Energizing was the way one author described her. “Obstacles never stopped her!” In every photograph I found she broadcasts an irresistible euphoria and is habitually well-turned-out in slacks, flats, and a Hermes scarf; she beams even in a photograph of her shoveling snow with Annie from around the tires of her Simca Aronde. In another, she is kneeling in front of her Jaguar MKII next to Annie and her full-grown leopard.

I have two favorites. In one, she is hand cranking a tire jack in a knee-length, fur-trimmed black astracan coat at some point during the 1960 Monte Carlo rally. In the other, she brims with enthusiasm; she is dressed for a costume ball in a white Cossack-style outfit with sash, boots, and turban that she made. She has a fake mustache and clutches a dagger in her mouth, one in each hand, her arms are raised as if ready to dance or attack.

The Monte Carlo race in ’56, after completing the first stage from Paris to Monaco, cut across five regions in southeastern France north of Monaco: the Alpes-Maritime, Ardeche, Drome, Haut Alpes, and Alpes-de-Haut-Provence. The race is in January when extreme climatic conditions are the norm. Heavy, wet snow, fog, ice, and mountain climbs over zig-zag switchbacks challenged every driver and navigator. It was a tough test for her first rally.

Louisette drove, Germaine advised, and Annie piloted. She handled roadmaps, dictated miles per hour parameters, and kept track of the stop watch to make sure they didn’t run afoul of the control points along the route. She gave instructions to Louisette that enabled her to maximize their speed and minimize hazards to them and the car. Teamwork was essential.

Rally racing is not an all-out dash to the finish line but it’s not a trip to the market either. It’s dangerous and during Louisette’s early racing years a driver had to have nerve, upper body strength, there was no power steering, and strong legs, or power brakes, to control the mechanics of the vehicle. The Simca was bulky, its steel construction made it heavy, it had rear wheel-drive making it harder to maneuver in wet or snowy conditions, single bulb headlights, it lacked side-view mirrors, and it was loud; even the gearbox required a strong grip to move the clutch. It was a lot of car to handle at high speeds but it was the kind physical test her peers said she excelled at. Moreover, her first years demonstrate a king-size tenacity.

She raced continually during the next years returning to Monte in ’59, ’60, and ’62. In 1960 she placed 1st in her biggest win up until then, in the Stuttgart-Lyon-Charbonieres Women’s Cup or “Le Charbo”, in her new Alfa Romeo Giulia T1 with Annie; one of France’s oldest and notably prestigious rallys. Annie drove this time and Louisette navigated the course from Stuttgart to Lyon-Charbonieres. Her debut in the Tour de France was in 1957 in her Simca and in 1961 she drove her Alfa and paired with Marie-Louise Mermod. In the 11th Tour de France in ’62 she was back with Annie in her Alfa T1 and in the 12th Tour in ’63 they took 2nd place in the Women’s Cup in Louisette’s metallic blue Jaguar MK II.

Her top performance in the Tour was the 13th in September 1964. She paired again with Mermod in her Jag but this time instead of crashing to avoid a flock of sheep and breaking her arm like in ’61, they took 1st place in the Tour’s Women’s Cup, 2nd in the women’s overall, and 17th in the combined men’s and women’s rankings.

The ’64 Tour is exemplar of the true essence of cross-country rallying. The 6,060 km/3,765 mile-course traversed the country in six stages over ten days that September; Louisette at the wheel and Marie-Louise in the jump seat navigating. They started in Lille in the north and raced south to Reims-210 km; stage two – Reims east to Caen-1,080; three – Caen south to Pau-1,440; four – Pau northeast to Aurillac-1,270; five – Aurillac east to Grenoble-1,610; and six – Grenoble south to Nice-450.

The nuts and bolts I found in Part 1 didn’t give me the answers I needed for Part III. My expectation of understanding Louisette’s driving obsession by understanding her childhood panned out on a hypothetical level but missed the mark in concrete terms. What did Jean Behra say that day at Montlhery that dazzled her so deeply? Enthusiasm and vehemence are as evanescent as champagne bubbles and the sound of engines revving is the background noise of daily life. What made that day so different? She was a strong, independent business woman who was very successful and only took vacations from her business to rally. Was she searching for something else while she raced all over the world? Where was she going emotionally? What was she chasing?

Questions tumbled around my head for days. Did racing offer an escape? Did she want to escape? Did she love cars as a kid because of what they represented? At any age, cars mean freedom to go anywhere you want anytime. She’d escaped the confinement of boarding school life and left the orphanage in the dust for an uncertain life dancing in cabarets. Maybe driving on the edge of a cliff felt the same? Always an unexpected, deep ravine at the bottom of every hairpin curve, every night on stage a daring or risky adventure. Maybe as an orphan she had to learn how to be comfortable with not knowing the future and came to enjoy the instability as an adult?

After the impermanence of orphanage life, I think the racing world was a place that gave her a sense of belonging, and where more constant, lasting friendships could develop. I think she liked the camaraderie of women in a sport dominated by men and to be in the company of people that she could depend on in life and on the track. I think she loved it because she was great and the exhilarating speed and smell of burning gas and rubber were indeed, an end in themselves. I think she loved it because racing cars was a way of taking control.

Earlier in the interview Louisette said that It was difficult being a woman at that time on racing circuit. “You had to be brave, courageous to drive at that time.” Her thoughts regarding women in the driver’s seat were sincere even though the linkages were tenuous and fraying. “Women supported each other, those that were racing, we were good friends.” A moment or two later she continued. “I looked for a girl who would be strong enough to race with me.” When I went through her race records it was easy to see that she found champions with the requisite prowess: Lise Renaud, Regine Gordine, Gilberte Thirion, Monique Bouvier, and Poupette Marmose.

Louisette cast her eyes around the room when we asked if she remembered her Jag, her favorite car. After William repeated the question a few times she perked up and said “Oh yes, I remember,” but her response sounded liked a false memory intended to please him.

The day was getting harder and my clock-watching didn’t help Xavier push through. She turned her head side to side like she was watching the car drive by or looking for someone. Things were unravelling; her thoughts were sliding around curves on some imaginary roadmap. Then without warning her autobiographical one-liner popped out like a champagne cork in the winner’s circle “I was racing and I’ve never stopped.” and there it was, Part III’s answer, and it wasn’t just about cars.